Maternal Mortality - A case study

In January 1995, I was appointed chief technical adviser under WHO/UNFA Strengthening Reproductive Health Services programme in Papua New Guinea (PNG). The project had the responsibility to work in four provinces in the country.

Health services were scarce and only available in towns. Emergency obstetric care was only available in provincial hospitals, which could be anything from few hours’ drive to several days of travel. Mountainous regions with poor roads and small islands scattered in vast sea areas of the country make it difficult to get adequate medical assistance for medical emergencies, especially during childbirth. The most pressing problem in PNG was very high pregnancy related maternal and neonatal mortality. Reliable figures were hard to come by but the maternal mortality ratio estimates ranged anything between 500-1000 per 100,000 live births. As expected, rural and remote areas bore much higher burden of mortality compared to urban areas. There was urgent need to get emergency obstetric care within reach.

Health service provision in the country was through primary health centres (PHCs) and district hospitals (DHs). Villages were served by Aid-posts manned by an aid-post orderly (auxiliary health workers) for first aid. PHCs were merely minor illness care centres, providing very elementary illness and some preventive services like antenatal care and vaccines to those who cared to visit the PHCs. Most of the births traditionally happened at home or even sending the women in labour alone into the bush, according to the local custom. A few women with difficult deliveries went to the health centres and were only referred to higher centres. Delays often caused deaths of mother or the baby or both. DHs were a bit better, especially if run by churches. Very few were equipped to provide essential obstetric care. Interventive procedures in obstetric care were largely restricted to the provincial hospitals, where surgical and blood transfusion facilities existed. With the knowledge that around 15% of all women in labour will end up with complications of pregnancy requiring emergency obstetric care (EOC) and at least 5-7% of these births requiring caesarean section, solutions to address the problem had to be found.

Obstacles to appropriate health service delivery in the time of need:

These difficulties and further complicated by the classical “three delays”, (1) deciding to seek appropriate medical help for an obstetric emergency; (2) reaching an appropriate obstetric facility; and (3) receiving adequate care when a facility is reached, lead to further discussions and decision to find possible solutions. To address these problems, a workshop was organised inviting selected participants to explore the causes of unacceptable maternal mortality in the country and to find solutions to address the situation. Care was taken in selecting participants who would have the expertise and good understanding of the problems faced in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, local experience of real situation in the field and knowledge and understanding of the local culture and habits of the people. Balance had to be struck between what was the ideal treatment and what was possible with limited facilities and skills of health workers at the health centre to ensure best chances of survival of the mother and the newborn.

Participants in the Workshop:

1. Senior Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital and Medical School. PNG national.

2. Epidemiologist from Community Medicine, University Hospital and Medical School. Indian National.

3. Senior Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, Provincial Hospital. PNG National.

4. Senior Medical Officer, Lutheran District Hospital. Madagascar National.

5. Four experienced midwives, from health centres in the project area. PNG National.

6. Two Health Centre OICs, from health centres in the project area. PNG National.

7. Two experienced aid-post orderlies, from aid-posts in the project area. PNG National.

8. Chief Technical Adviser – Initiator and organiser WHO/UNFPA. Indian National.

The first task was to decide the most common complications of pregnancy arriving at health centres and how best they could be managed and referred to provincial hospitals. It was easy to list the most common complications of pregnancy as the participants had experienced the death and misery of women arriving at health centres and not being able to do much to save lives. Most critical reason for maternal mortality was judged to be the delay in receiving required medical intervention in any complications of pregnancy.

Complications of Pregnancy seen at health facilities:

Interesting discussions emerged during the workshop between the experts and midwives when, for example, someone suggested blood transfusion for the bleeding mother. The health center workers quickly reminded that there were no facilities for transfusion or cross match at the health center. The principle to be followed was to stabilize the mother with whatever was available at the health center and transfer the patient to provincial hospital for further treatment. Considering the minimum survival time available for a complication, the health center staff had to develop a treatment protocol which will sustain her until she is transferred to the referral hospital within that time to ensure possibility of survival.

It was also decided that each complication of pregnancy should have instructions for the health worker at the PHC limited to a single A4 sheet of paper, as much more detailed instructions are difficult to follow in a small labour room by limited skilled staff attending the patient.

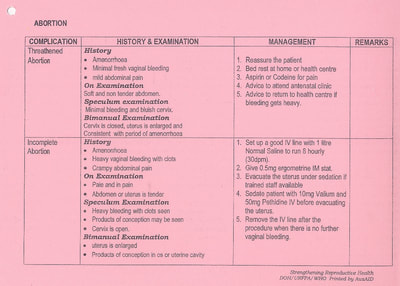

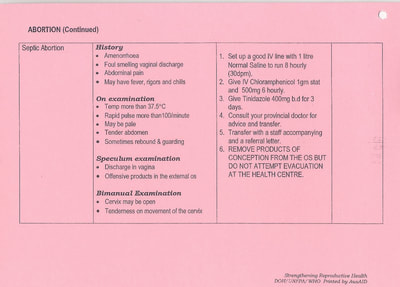

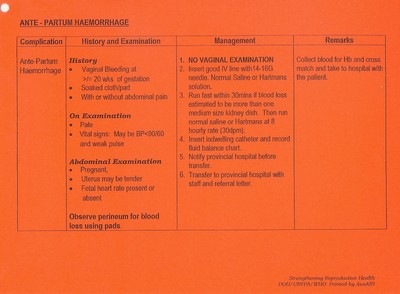

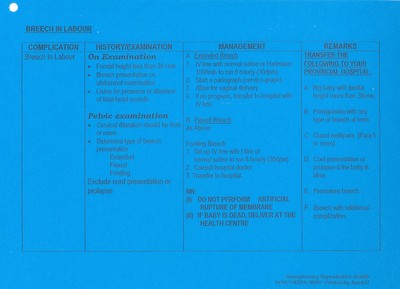

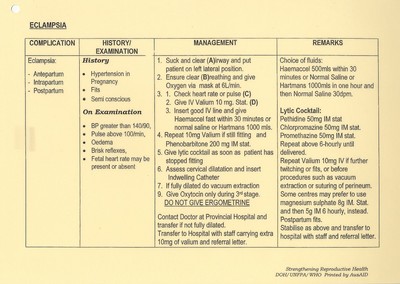

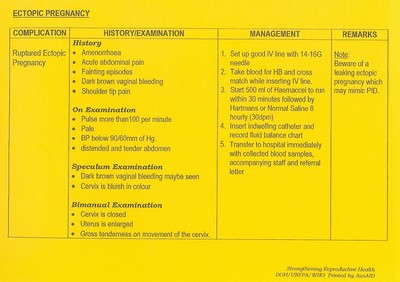

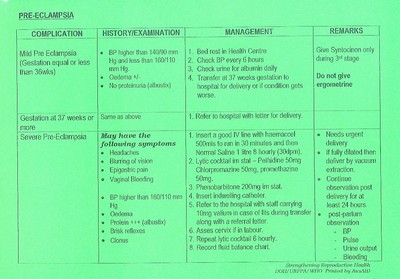

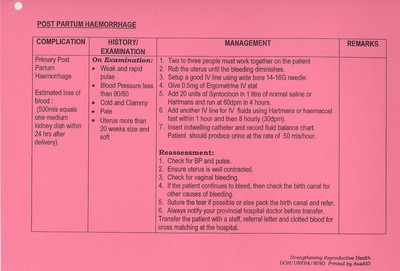

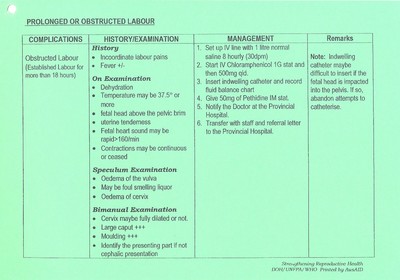

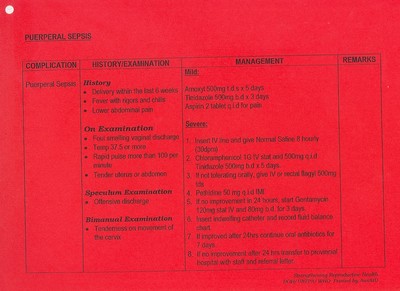

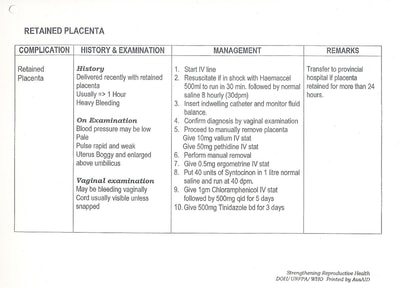

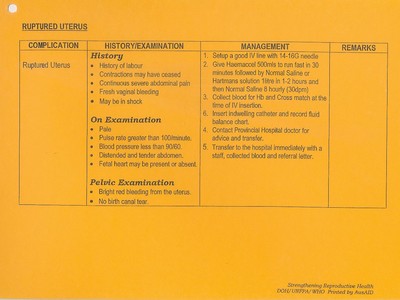

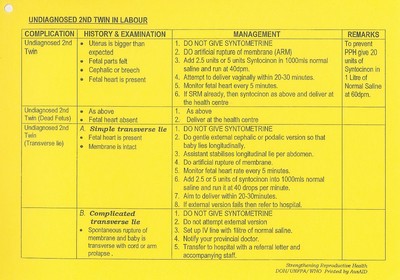

At the end of the workshop one page protocols were developed and decision was made to laminate each one and ring them together. Protocols were also colour coded according to the urgency of the complication. The ringed protocols were then hung prominently on the obstetric bed so that health worker attending the patient can read and follow instructions without having to touch it. (see details of the protocols below)

Post Script

These instructions/protocols were a great success and are still used with necessary updates in all health facilities in PNG. This approach was further applied, after appropriate modifications in Laos, greatly appreciated by district health staff. Protocols were developed in 1995 and many improvements are applicable today. For example antibiotics listed or blood transfusion over time could be made possible with limited facilities. The 2020 WHO guidelines affirm that misoprostol can save lives in PPH and its availability in health centers is a must along with training of its proper use to HC staff. HIV infection was not considered at that time but with advanced treatment available now changes can be made to improve the outcome of pregnancy. Similarly, medical treatment for Eclampsia has advanced greatly since then.

The fact remains that even today the principle of this approach is applicable in many instances and situations. Maternal mortality and early neonatal mortality remains a major problem in many developing countries where full obstetric services cannot be established for all remote and sparsely populated populations. The need for stabilising a critically ill patient and quick and efficient transfer to a hospital where further treatment can be provided is the key to save lives. This is not only applicable to obstetric complications but also to any critically ill patient or an accident victim.

In January 1995, I was appointed chief technical adviser under WHO/UNFA Strengthening Reproductive Health Services programme in Papua New Guinea (PNG). The project had the responsibility to work in four provinces in the country.

Health services were scarce and only available in towns. Emergency obstetric care was only available in provincial hospitals, which could be anything from few hours’ drive to several days of travel. Mountainous regions with poor roads and small islands scattered in vast sea areas of the country make it difficult to get adequate medical assistance for medical emergencies, especially during childbirth. The most pressing problem in PNG was very high pregnancy related maternal and neonatal mortality. Reliable figures were hard to come by but the maternal mortality ratio estimates ranged anything between 500-1000 per 100,000 live births. As expected, rural and remote areas bore much higher burden of mortality compared to urban areas. There was urgent need to get emergency obstetric care within reach.

Health service provision in the country was through primary health centres (PHCs) and district hospitals (DHs). Villages were served by Aid-posts manned by an aid-post orderly (auxiliary health workers) for first aid. PHCs were merely minor illness care centres, providing very elementary illness and some preventive services like antenatal care and vaccines to those who cared to visit the PHCs. Most of the births traditionally happened at home or even sending the women in labour alone into the bush, according to the local custom. A few women with difficult deliveries went to the health centres and were only referred to higher centres. Delays often caused deaths of mother or the baby or both. DHs were a bit better, especially if run by churches. Very few were equipped to provide essential obstetric care. Interventive procedures in obstetric care were largely restricted to the provincial hospitals, where surgical and blood transfusion facilities existed. With the knowledge that around 15% of all women in labour will end up with complications of pregnancy requiring emergency obstetric care (EOC) and at least 5-7% of these births requiring caesarean section, solutions to address the problem had to be found.

Obstacles to appropriate health service delivery in the time of need:

- Absence of adequate facilities for women with complications of pregnancy in the PHCs and DHs;

- Lack of skilled health workers in health facilities;

- Time taken to reach provincial hospitals due to long distances and/or poor roads, including sea travel from islands;

- Transport difficulties, land, sea and air;

- Cost of travel to referral hospitals.

These difficulties and further complicated by the classical “three delays”, (1) deciding to seek appropriate medical help for an obstetric emergency; (2) reaching an appropriate obstetric facility; and (3) receiving adequate care when a facility is reached, lead to further discussions and decision to find possible solutions. To address these problems, a workshop was organised inviting selected participants to explore the causes of unacceptable maternal mortality in the country and to find solutions to address the situation. Care was taken in selecting participants who would have the expertise and good understanding of the problems faced in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, local experience of real situation in the field and knowledge and understanding of the local culture and habits of the people. Balance had to be struck between what was the ideal treatment and what was possible with limited facilities and skills of health workers at the health centre to ensure best chances of survival of the mother and the newborn.

Participants in the Workshop:

1. Senior Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital and Medical School. PNG national.

2. Epidemiologist from Community Medicine, University Hospital and Medical School. Indian National.

3. Senior Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, Provincial Hospital. PNG National.

4. Senior Medical Officer, Lutheran District Hospital. Madagascar National.

5. Four experienced midwives, from health centres in the project area. PNG National.

6. Two Health Centre OICs, from health centres in the project area. PNG National.

7. Two experienced aid-post orderlies, from aid-posts in the project area. PNG National.

8. Chief Technical Adviser – Initiator and organiser WHO/UNFPA. Indian National.

The first task was to decide the most common complications of pregnancy arriving at health centres and how best they could be managed and referred to provincial hospitals. It was easy to list the most common complications of pregnancy as the participants had experienced the death and misery of women arriving at health centres and not being able to do much to save lives. Most critical reason for maternal mortality was judged to be the delay in receiving required medical intervention in any complications of pregnancy.

Complications of Pregnancy seen at health facilities:

- Abortion

- Antepartum Haemorrhage;

- Post-partum Haemorrhage ;

- Retained Placenta;

- Obstructed Labour;

- Breech Presentation;

- Twin or Multiple Pregnancy;

- Eclampsia;

- Ruptured Uterus;

- Puerperal Sepsis;

- Ectopic Pregnancy.

Interesting discussions emerged during the workshop between the experts and midwives when, for example, someone suggested blood transfusion for the bleeding mother. The health center workers quickly reminded that there were no facilities for transfusion or cross match at the health center. The principle to be followed was to stabilize the mother with whatever was available at the health center and transfer the patient to provincial hospital for further treatment. Considering the minimum survival time available for a complication, the health center staff had to develop a treatment protocol which will sustain her until she is transferred to the referral hospital within that time to ensure possibility of survival.

It was also decided that each complication of pregnancy should have instructions for the health worker at the PHC limited to a single A4 sheet of paper, as much more detailed instructions are difficult to follow in a small labour room by limited skilled staff attending the patient.

At the end of the workshop one page protocols were developed and decision was made to laminate each one and ring them together. Protocols were also colour coded according to the urgency of the complication. The ringed protocols were then hung prominently on the obstetric bed so that health worker attending the patient can read and follow instructions without having to touch it. (see details of the protocols below)

Post Script

These instructions/protocols were a great success and are still used with necessary updates in all health facilities in PNG. This approach was further applied, after appropriate modifications in Laos, greatly appreciated by district health staff. Protocols were developed in 1995 and many improvements are applicable today. For example antibiotics listed or blood transfusion over time could be made possible with limited facilities. The 2020 WHO guidelines affirm that misoprostol can save lives in PPH and its availability in health centers is a must along with training of its proper use to HC staff. HIV infection was not considered at that time but with advanced treatment available now changes can be made to improve the outcome of pregnancy. Similarly, medical treatment for Eclampsia has advanced greatly since then.

The fact remains that even today the principle of this approach is applicable in many instances and situations. Maternal mortality and early neonatal mortality remains a major problem in many developing countries where full obstetric services cannot be established for all remote and sparsely populated populations. The need for stabilising a critically ill patient and quick and efficient transfer to a hospital where further treatment can be provided is the key to save lives. This is not only applicable to obstetric complications but also to any critically ill patient or an accident victim.